Twilight of the Belle Epoque by Mary McAuliffe

History (2014 - 350 pp.)

Twilight of the Belle Epoque is the second in Mary McAuliffe's two-part series on France between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I (1871-1918). I reviewed the first book, Dawn of the Belle Epoque, in 2017; Dawn takes the reader from the ashes of Paris in 1871 to the stunning splendour of the 1900 Paris Exposition. Twilight of the Belle Epoque takes the reader from the Exposition* to, and through, France's devastating experience of World War I. Fittingly, Twilight of the Belle Epoque opens with Pablo Picasso, age nineteen, stepping off the train to see his painting on display at the Exposition, (5) and ends with the 1918 Victory Day parade. Oh, how things changed in those critical eighteen years...

The earliest years of the 1900s saw innovation and splendour. The 1900 Paris Olympics, only the second games since their modern restoration four years earlier, featured sports like croquet (11). Georges Melies's groundbreaking 1902 film A Trip to the Moon was an astonishing fourteen minutes long, featured some of the first special effects, (68) and has a legacy long enough to be parodied in the music video for the Smashing Pumpkins' 1995 hit "Tonight, Tonight". Citroen and Renault, two still-around auto manufacturers, rank among the key figures McAuliffe tracks from their early racing days to their gargantuan World War I military supply efforts. Gabriel Voisin, an early airplane manufacturer, made France briefly the world's dominant air power. Louis Bleriot crossed the English Channel on a monoplane in 1909. (189-190)

Innovation in the Belle Epoque was not limited to the manufacturing sector. Pierre and Marie Curie's co-discovery of radium leads McAuliffe to an in-depth discussion of Marie's life after Pierre's death, from her scandalous affair with fellow scientist Paul Langevin to her effort bringing X-rays to the war front. (278) Francois Coty dominated the perfume market with a high-quality product sold in attractive bottles: "Even at the beginning, his formulas were simple but brilliant, using synthetics to enhance natural scents." Coty said of his bottles, "A perfume needs to attract the eye as much as the nose." (92) Meanwhile, Coco Chanel simplified women's clothing with inspiration from menswear, which aided the death of the corset. (235)

Prominent figures from Dawn of the Belle Epoque re-emerge in Twilight of the Belle Epoque as elder statesmen. The period between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I, at 43 years long, is over half the length of the average life span; someone born immediately after the Paris Commune would often be married with children by 1914. Seeing Sarah Bernhardt "sixty-six and a grandmother", (202) Edgar Degas "an old man and almost blind" (225) in his 70s, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet worrying for their sons during World War I, (285) or Auguste Rodin be chased by a woman over fifty years his junior (317) is jarring when considering how few pages McAuliffe requires to get them there.

The period before and during World War I saw violence, epidemics, and all manner of afflictions. Not everyone could live, like Rodin, to old age. Carles Casagemas, a promising young Spanish painter and close friend of Picasso, died in 1901 of a self-inflicted gunshot wound during a dinner party in what has to be one of the book's most thrilling scenes. (40) Pierre Curie, co-discoverer of radium, died from being hit by a car in 1905. (147-148) The poet Charles Peguy died from a bullet to the forehead during World War I. (285)

Nonetheless, the Belle Epoque was a joyful era for many. Twilight of the Belle Epoque charts Claude Debussy's dominance and Maurice Ravel's launch into superstardom, starting with a few key etudes like Ravel's 1901 "Jeux d'Eau". In 1905, nearing the peak of his fame, Ravel stated that "I have never been so happy to be alive, and I firmly believe that joy is far more fertile than suffering." (113) Russian ballet swept across Paris, with impresario Sergei Diaghilev and dancer Vaslav Nijinsky among the most coveted artists. Diaghilev approached Debussy and Ravel to write music for his ballets, with mixed success, (188) but it was a young Igor Stravinsky who wrote the score for the 1910 hit The Firebird. (202)

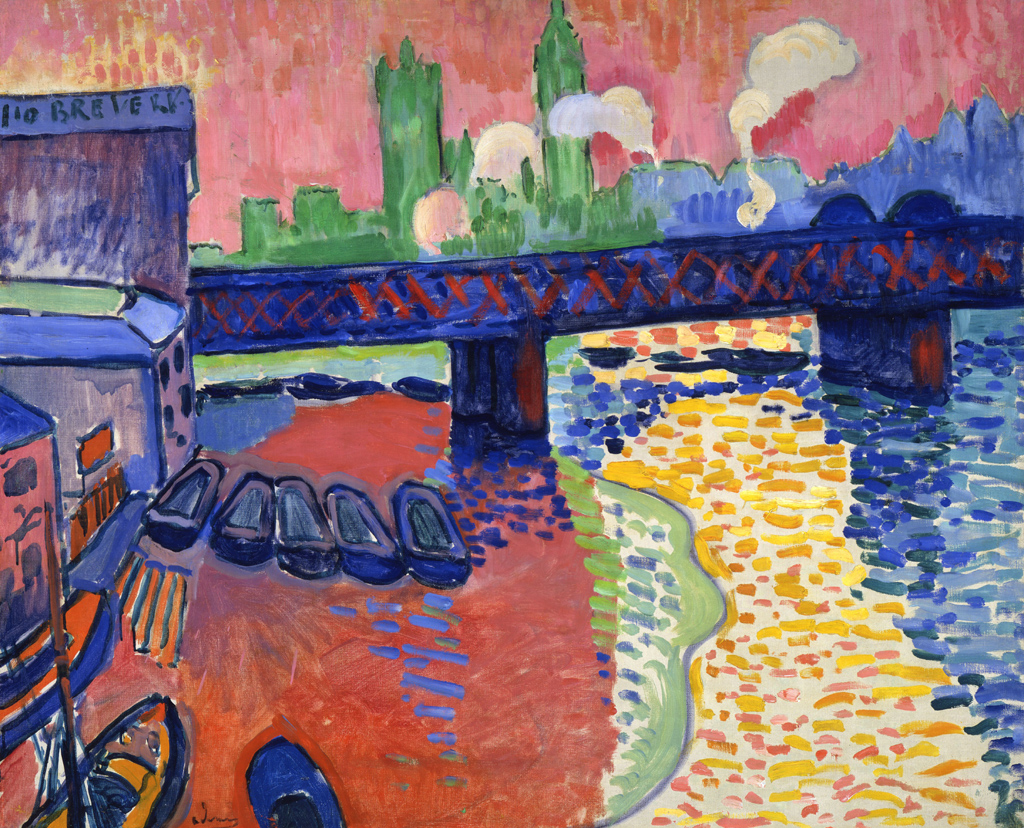

One of the dominant movements in painting was the short-lived Fauvism, the art of wild beasts. Henri Matisse and Andre Derain were the main names in this movement, with many of their paintings from the 1905-1908 period selling for millions or being retained in museums today.** For example, Derain's Charing Cross Bridge (1905) was displayed at the Salon d'Automne in 1905:

|

| Andre Derain, Charing Cross Bridge, 1905. Image from Wikipedia. |

McAuliffe's focus is usually on artistic and social movements, so reading about World War I picked my attention right back up after so many pages on the few years preceding it. McAuliffe follows Charles De Gaulle from his childhood early in the book until his days as a captain during World War I, impressing his superiors by advocating for aggressive battlefield tactics. De Gaulle's most notable adventure, though, happens after his capture by German forces. His multiple prison escapes are worthy of an action movie; one escape in Bavaria, when De Gaulle escaped by hiding in a laundry basket, has decidedly The Count of Monte Cristo feel.

Although McAuliffe makes the reader yearn for the Belle Epoque, Midnight in Paris-style, she turns 180 degrees on the very last page. She points out that for Paris's poor, the Belle Epoque was a miserable time; (350) the biographies of some of her selected celebrities who fell into poverty echo this sentiment. Melies, the great filmmaker, lost almost all of his money when his master tapes were melted for their metal content during World War I. He shifted occupations, shockingly, to owning a candy and toy store. (332-333) Picasso had to wait until 1909 to rent a large, clean apartment with a maid (178), nine years after disembarking the train on the opening page, after his Blue Period had already ended and Cubism was underway. The Belle Epoque could be as dazzling as the 1912 Paris social scene's "new standard for reckless extravagance" (229) or as horrifying as the war that Edith Wharton, referring to German actions in Belgium, called a "hideous flood of savagery". (277) The ominous feeling for the reader of knowing how soon World War I will occur, while the characters have no way of knowing, makes each chapter feel precious. With each chapter covering roughly a year, time is limited by the physical pages of the book.

Ease of Reading: 4

Educational Content: 8

*Footage is on YouTube.

**Matisse's Femme assise sue on balcon (a non-Fauvist painting) could only fetch $3 million CAD earlier this year, which was below the consignor's reserve price, so the painting did not sell. Prognosticators estimated the painting to fetch $3.8-$5.8 million earlier that week.

**Matisse's Femme assise sue on balcon (a non-Fauvist painting) could only fetch $3 million CAD earlier this year, which was below the consignor's reserve price, so the painting did not sell. Prognosticators estimated the painting to fetch $3.8-$5.8 million earlier that week.

No comments:

Post a Comment